This article had its genesis when co-author Ed’s dog, Sparkle, was treated for pneumonia in the summer of 2024. Ed, a mathematician and chair of the Alliance for Data Science Professionals, was intrigued by the surgery’s use of data in Sparkle’s treatment and decided to find out more about the use of data and AI in veterinary medicine. His exploration led to a guest appearance on the Vet Voices on Air podcast hosted by co-author Robyn. She is a registered veterinary nurse (RVN) and the director of Veterinary Voices UK. Inspired by that conversation, this article explores the ways veterinary professionals are currently applying data science principles and how professions adapt and evolve in the face of these developments.

The use of AI and the data science that underpins and enables it are growing in ubiquity, and one area that is embracing these approaches is veterinary medicine.

Unlike human medicine in the UK, veterinary medicine is not organised under a centralised system such as the National Health Service (NHS). Instead, veterinary care is delivered through a variety of business structures, including Joint Venture Practices, Independent, Corporate, and Charity. These structures differ not only in ownership and funding but also in the scope and services that the practices provide. In many cases,the availability of more specialised care may depend on the expertise of individual(s) within the practice. Broadly speaking, practices tend to include: farm animals; exotics; equine; small animal; and mixed. Some practices will cover zoological work, conservation work and invertebrate work among other specialties.

Veterinary surgeons and RVNs are also employed in academia, conducting applied research in industry or government, and as advisors in government agencies.

Data in the Veterinary Profession: Challenges and Opportunities

If Artificial Intelligence (AI) is to be used in any sphere, it needs to be trained on data. The data used to train should be relevant, complete, structured, accurate, consistently formatted, and labelled. Achieving this standard is a challenge not only in veterinary medicine but also in many other fields where data are fragmented and inconsistently recorded. In the veterinary profession, unlike centralised NHS data, the veterinary data are often stored in individual practices or farms. These may use different formats and scales (such as imperial or metric), US or UK date formats, and twelve or twenty-four hour clocks. These records may also fail to follow the animal if it is sold or moves to a new practice. Such inconsistencies mirror the difficulties faced in other domains, and can make the adoption of AI in veterinary medicine particularly complex..

On the other hand, animal data has fewer constraints than human data. Article 4 of the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) makes it clear that the act applies to ‘personal data’ and specifies that ‘an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified’, which means that there is potentially more freedom to use data related to animals than humans. (It is worth noting that the GDPR would apply to the farmer, pet owner, or veterinary staff involved, so some consideration might still be required.) Given this data is an asset, it is worth considering whether it is owned by the animal’s owner or the veterinary professional (or their employer) in any given circumstance.

How AI is Already Transforming Veterinary Practice

AI is becoming an affordable and widely used tool in veterinary medicine. It’s now commonly applied in areas like diagnostics, treatment, and disease monitoring and prediction, despite the misconception that it’s rarely used. Preventative healthcare has always been a key aim within veterinary medicine. The obligation to ensure that both animal health and welfare and public health are accounted for is reflected by point 6.1 of the Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Surgeons and RVNs: ‘6.1 Veterinary surgeons must seek to ensure the protection of public health and animal health and welfare’.

Diagnostics

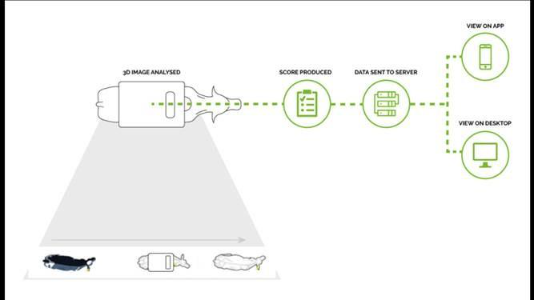

Diagnosis and prediction of diseases is one key area where AI is being used in veterinary medicine in farm animals, companion animals and beyond.

For example, in companion animals AI has been used to assist in the diagnosis of canine hypoadrenocorticism, an endocrine disease. Additionally, machine learning algorithms have potential for improving the prediction and diagnosis of leptospirosis, an infectious zoonotic disease. Additionally, by combining MRI data with facial image analysis, an AI tool can assist in predicting the likelihood of chiari like malformation (CM) and syringomyelia (SM) from images of the dog’s head obtained via an owner’s smartphone. And finally, AI can also assist with faecal analysis: images are analysed by proprietary Artificial Intelligence models which reference the images against the Telenostic Reference Library, a company specialising in parasitology diagnostic solutions. The image recognition software identifies each specific parasite species and the number of parasitic eggs or oocysts present.

These are just a few examples of AI use in companion animals currently.

Disease Monitoring and Prediction Disease monitoring and prediction are exciting because they can help us act earlier—sometimes even preventing illness. This not only improves animal health and welfare, but also supports antimicrobial stewardship by reducing unnecessary treatments, helping to combat antimicrobial resistance—a serious global threat to both animals and humans.

An area that demonstrates compelling evidence of these positive outcomes is farming and agriculture, where farmers are able to use AI to monitor herds, and act promptly to treat disease, before it would have been evident and notable by human monitoring. Examples, which will be explored in more detail below, include body condition technology, lameness technology, disease recognition, grazing, land and pasture management, biosensors and biochips and more.

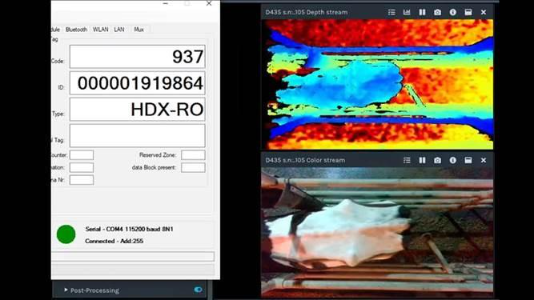

Body Condition Technology The agricultural industry typically relies on subjective visual observation, human recording and manual reporting of all the key health and welfare traits, including Body Condition Score (BCS). Despite these individuals being highly skilled professionals, there is inevitable human error, paired with the constraints of busy farm management which can lead to cases getting picked up later in their disease process. BCS is a major indicator of metabolic performance in dairy cows and directly related to fertility performance and health traits. Technologies such as Herdvision use a 2D and 3D camera system to monitor BCS, resulting in improvement in cattle heath and fertility, less premature culling, and savings on feeding costs.

Lameness Technology

Lameness is considered one of the top cattle health and welfare challenges. A 2013 study noted that almost 70% of the dairy farmers expressed an intention to take action for improving dairy cow foot health. Cattle naturally mask the signs of pain, and as with body condition scoring we have relied on subjective visual observation, human recording and manual reporting of all the key health and welfare traits. Technology that can pick up lameness earlier, with more objectivity and with less labour intensity is hugely beneficial to both the animals’ health and welfare and the farm’s profitability.

Disease Recognition As with lameness assessments, monitoring of pain in the UK pig industry relies on human observation, either in person or via video footage, to detect disease.

An interdisciplinary team at the Newcastle University have used artificial intelligence to develop automated systems to analyse and monitor pig behaviour and health. The algorithm was tested in a controlled environment where infection and disease were present, assessing footage of pigs captured by cameras and pinpointing and quantifying changes in behaviours to identify links to disease.

Other computer vision and AI-based approaches have allowed the automatic scoring of pigs in relation to posture, aggressive episodes, tail-biting episodes, fouling, diarrhoea, stress prediction in piglets, weight estimation, and body size – all providing animal farmers increased insight into the health of their population.

Grazing, Land and Pasture Management The use of AI has allowed more efficient pasture and grazing management, allowing movement of livestock onto new pastures when the grazing quality and quantity depletes below a certain threshold.

There are numerous methods of using Agri-Tech to monitor animals, such as the SheepIT project, an initiative where an automated IoT-based system controls grazing sheep. Typically, such solutions are split into two main groups: location monitoring and behaviour and activity monitoring. Location monitoring allows farmers to keep track of animals, inferring preferred pasturing areas and grazing times, and even detecting absent animals. Behaviour and activity monitoring focuses on detecting the type and duration of an animal’s activities – for example resting, eating or running - based on accelerometry and audiometry.

Biosensors and Biochips In human medicine, advances in molecular medicine and cell biology have driven the interest in electrochemical systems to detect disease biomarkers and therapeutic compounds (medications for example). Currently in human literature, implantable biosensors have been noted in glucose monitoring, DNA detection and cultures, among others. Microelectronic technology offers powerful circuits and systems to develop innovative and miniaturised biochips for sensing at the molecular level; these have numerous applications in veterinary medicine from hormone detection, pathogenic microorganism and infection monitoring and homeostatic mechanism surveillance (homeostasis being the bodies regulatory mechanisms that controls many functions and maintain stability) such as being applied to pathogen detection in cattle mastitis.

Paul Horwood, Farm Vet and Founder of AI(Live), a conference on the development of AI applications in the livestock industry, sees this as a time of opportunity for the profession:

“The farm vet’s role continues to evolve from”problem-solver after the fact” to “strategic advisor at the heart of herd health planning.” Technology is helping us get there by giving us earlier insights, better data, and stronger evidence for the decisions we make every day. We’re at a pivotal moment. The technology is here. The challenge is knowing how to use it and how to lead with it. As a farming nation, we have always been innovative; as farm animal veterinary surgeons, we can either wait to be brought in at the end of the conversation, or step forward now to shape how AI is used on UK farms. Let’s choose the latter.”

Shared Frontiers: Common Threads in AI Adoption Across Sectors

The veterinary sector, like every other industry, is on a journey when it comes to the use of artificial intelligence, and many of the themes that are emerging are common to other sectors.

For veterinary professionals this includes:

- The need to radically change training of new vets and RVNs to ensure that they are prepared to embrace the new opportunities that AI will bring.

- The need to upskill existing vets and RVNs to enable them to use these new opportunities.

- Working with stakeholders, such as in this case farmers and pet owners, to evolve the business model to ensure that all parties benefit from the change.

- A change in the attitude to data, in which it becomes seen as a business asset when it is well managed, with the ultimate benefit in this sector of promoting the wellbeing of animals.

These recurring patterns offer a blueprint for understanding how professions evolve in response to developments in the field, and a reminder that AI isn’t just transforming high-tech labs and Fortune 500 boardrooms – it is quietly revolutionising industries across every sector. By looking at how specific professions, like veterinary, are navigating this shift, we can better understand the broader dynamics at play when machine learning meets existing practice.

Bridging Disciplines: Unlocking Value Through Interdisciplinary Collaboration

This is a pivotal moment where the intersection of data science and veterinary medicine offers a unique opportunity for cross-sector collaboration, driving progress in both fields.

The field of data science has much to offer industries currently experiencing these inflection points. Although many data scientists come from ‘traditional’ backgrounds such as statistics, mathematics, or computer science graduates, many more diverse routes to data science roles now exist. These routes include people who wouldn’t necessarily call themselves data scientists who work in other professions who use data science in their working life, upskilling themselves through training, or even trial and error. The authors are already aware of veterinary professionals who are skilled data scientists, even if they may not identify as such, applying data science to veterinary research in academia or industry. The RSS, other professional bodies within the Alliance for Data Science Professionals, and Data Science departments in universities may find offering Continuous Professional Development opportunities to the veterinary profession worthwhile. Certainly, the certifications offered by the RSS of Data Science Practitioner and Advanced Data Science Practitioner are open to veterinary professionals who have developed such skills.

The veterinary profession may also provide benefits to the data science community, by providing data sets that can be applied in many ways without major GDPR issues, as well as opportunities to showcase the benefits of data science to society and animal health and welfare through examples similar to those above.

One vehicle for more cross-pollination could be joint conferences. A near-term opportunity is AI (Live) in September 2025, which aims to start the debate and establish the principles by which AI and livestock farming can derive the maximum benefits, with a focus on education, governance and application.

By fostering collaboration across disciplines, we can ensure that the benefits of this data revolution are shared—by all creatures, great, small, and artificial. And we are happy to report that Sparkle, whose illness sparked this article, has made a full recovery and in fact recently celebrated her ninth birthday!

- About the author

- Robyn Lowe, BSc (Hons), Dip AVN (Surgery, Medicine, Anaesthesia), Dip HE CVN, RVN, is a registered veterinary nurse and Director of Veterinary Voices UK, a community of veterinary professionals fostering public understanding of veterinary and animal welfare issues. She hosts the organisation’s Vet Voices on Air podcast.

- Professor Edward Rochead, M.Math (Hons), PGDip, CMath, FIMA is a mathematician employed by the government, currently leading work on STEM Skills and Data. Ed is chair of the Alliance for Data Science Professionals, a Visiting Professor at Loughborough University, an Honorary Professor at the University of Birmingham, Chartered Mathematician, and Fellow of the IMA and RSA.

- Copyright and licence

- © 2025 Robyn Lowe and Edward Rochead.

Text, code, and figures are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) International licence, except where otherwise noted. Thumbnail image by Shutterstock/g/fotopanorama360 Licenced by CC-BY 4.0.

- How to cite

- Lowe, Robyn and Rochead, Edward. 2025. “All Creatures, Great, Small, and Artificial” Real World Data Science, August 22nd, 2025. URL