1 We Built Agentic Systems. Here’s What Broke.

When Agentic AI started dominating research papers, demos, and conference talks, I was curious but cautious. The idea of intelligent agents, autonomous systems powered by large language models that can plan, reason, and take actions using tools, sounded brilliant in theory. But I wanted to know what happened when you used them. Not in a toy notebook or a slick demo, but in real projects, with real constraints, where things needed to work reliably and repeatably.

In my role as Clinical AI & Data Scientist at Bayezian Limited, I work at the intersection of data science, statistical modelling, and clinical AI governance, with a strong emphasis on regulatory-aligned standards such as CDISC. I have been directly involved in deploying agentic systems into environments where trust and reproducibility are not optional. These include real-time protocol compliance, CDISC mapping, and regulatory workflows. We gave agents real jobs. We let them loose on messy documents. And then we watched them work, fail, learn, and (sometimes) recover.

This article is not a critique of Agentic AI as a concept. I believe Agentic AI has potential value, but I also believe it demands more critical evaluation. That means assessing these systems in conditions that mirror the real world, not in benchmark papers filled with sanitised datasets. It means observing what happens when agents are under pressure, when they face ambiguity, and when their outputs have real consequences. What follows is not speculation about what Agentic AI might become a decade from now. It is a candid reflection on what it feels like to use these systems today. It is about watching a chain of prompts unravel or a multi-agent system drop the baton halfway through a task. If we want Agentic AI to be trustworthy, robust, and practical, then our standards for evaluating it must be shaped by lived experience rather than theoretical ideals.

2 What Agentic AI Looks Like in Practice

If you’re imagining robots in lab coats, that’s not quite what this is. It is more like releasing a highly motivated intern into a complex archive with partial instructions, limited supervision, and the freedom to decide which filing cabinets, databases, or tools to open next. It is messy. It is unpredictable. And it sometimes surprises you with just how resourceful or confused it can get. Agentic AI systems are purpose-built setups where a large language model is given a task and enough autonomy to decide how to approach it. That might mean choosing which tools to use, when to use them, and how to adapt when things go off-script. You are not just sending one prompt and getting an answer. You are watching a system reason, remember, call APIs, retry when things go wrong, and ideally, get to a useful result.

At Bayezian, we have explored this in several internal projects, including generating clinical codes from statistical analysis plans and study specifications, monitoring synthetic Electronic Health Records (EHRs) for rule violations, and running chained reasoning loops to validate document alignment. These efforts reflect the reality of building LLM agents into safety-critical and compliance-heavy workflows. Across these deployments, the question is never just “can it do the task” but “can it do the task reliably, interpretably, and safely in context”.

Broader research has followed similar directions. In clinical pharmacology and translational sciences, researchers have explored how AI agents can automate modelling and trial design while keeping a human in the loop, and offering blueprints for scalable, compliant agentic workflows link. In the context of patient-facing systems, agentic retrieval-augmented generation has improved the quality and safety of educational materials, with LLMs acting as both generators and validators of content link. Other teams have used multi-agent systems to simulate cross-disciplinary collaboration, where each AI agent brings a different scientific role to design and validate therapeutic molecules like SARS-CoV-2 nanobodies link.

Some of the systems we built used agent frameworks like LangChain or LlamaIndex. Others were bespoke combinations of APIs, function libraries, memory stores, and prompt stacks wired together to mimic workflow behavior. Regardless of the architecture, the core structure remained the same. The agent was given a task, a bit of autonomy, and access to tools, and then left to figure things out. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes it did not. That gap between intention and execution is where most of the interesting lessons sit.

In the next section, I describe one of those deployments in more detail: a multi-agent system used to monitor data flow in a simulated clinical trial setting.

3 Case Study: Monitoring Protocol Deviations with Agentic AI

Why We Built It

Clinical trials generate a stream of complex data, from scheduled lab results to adverse event logs. Hidden in that stream are subtle signs that something may be off: a visit occurred too late, a test was skipped, or a dose changed when it shouldn’t have. These are protocol deviations, and catching them quickly matters. They can affect safety, skew outcomes, and trigger regulatory scrutiny.

Traditionally, reviewing these events is a painstaking task. Study teams trawl through spreadsheets and timelines, cross-referencing against lengthy protocol documents. It is time-consuming, easy to miss context, and prone to delay. We wondered whether an AI-driven approach could act like a vigilant reviewer. Not to replace the team, but to help it focus on what truly needed attention.

Our motivation was twofold. First, to introduce earlier, more consistent detection without relying on rule-based systems that often buckle under real-world variability. Second, to test whether a group of coordinated language model agents, each with a clear focus, could carry out this work at scale while still being interpretable and auditable.

To do that, we built the system from the ground up. We designed a pipeline that could ingest clinical documents, extract key protocol elements, embed them for semantic search, and store them in structured form. That created the foundation for agents to work not just as readers of data, but as context-aware monitors. Understanding whether a missed Electrocardiogram (ECG) or a delayed Day 7 visit violated the protocol required more than lookup tables. It required reasoning. It required memory. It required agents built with intent.

What emerged was a system designed not just to scan data, but to think with constraints, assess context, and escalate issues when the boundaries of the trial were breached. The goal was not perfection, but partnership. A system that could flag what mattered, explain why, and stay open to human feedback.

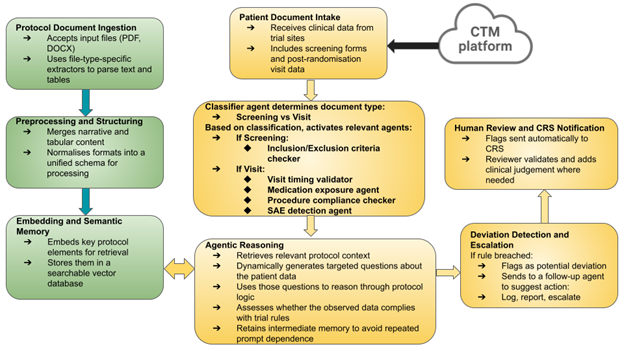

How It Was Set Up

The system was built around a group of focused agents, each responsible for checking a specific type of protocol rule. Rather than relying on one large model to do everything, we broke the task into smaller parts. One agent reviewed visit timing. Another checked medication use. Others handled inclusion criteria, missed procedures, or serious adverse events. This made each agent easier to understand, easier to test, and less likely to be overwhelmed by conflicting information.

Before any agents could be activated, however, an early classifier was introduced to determine what type of document had arrived. Was it a screening form or a post-randomisation visit report? That initial decision shaped the downstream path. If it was a screening file, the system activated the inclusion and exclusion criteria checker. If it was a visit document, it was handed off to agents responsible for tracking timing, treatment exposure, scheduled procedures, and adverse events.

These agents did not operate in isolation. They worked on top of a pipeline that handled the messy reality of clinical data. Documents in different formats were extracted, cleaned, and converted into structured representations. Tables and free text were processed together. Key elements from study protocols were embedded and stored to allow flexible retrieval later. This gave the agents access to a searchable memory of what the trial actually required.

While many agentic systems today rely heavily on frameworks like LangChain or LlamaIndex, our system was built from the ground up to suit the demands of clinical oversight and regulatory traceability. We avoided packaged orchestration frameworks. Instead, we constructed a lightweight pipeline using well-tested Python tools, giving us more control over transparency and integration. For semantic memory and search, protocol content was indexed using FAISS, a vector store optimised for fast similarity-based retrieval. This allowed each agent to fetch relevant rules dynamically and reason through them with appropriate context.

When patient data flowed in, the classifier directed the document to the appropriate agents. If any agent spotted something unusual, it could escalate the case to a second agent responsible for suggesting possible actions. That might mean logging the issue, generating a report, or prompting a review from the study team. Throughout, a human remained involved to validate decisions and interpret edge cases that needed nuance.

We did not assume the agents would get everything right. The idea was to create a process where AI could handle the repetitive scanning and flagging, leaving people to focus on the work that demanded clinical judgement. The combination of structured memory, clear responsibilities, document classification, and human oversight formed the backbone of the system.

Figure 1 illustrates a two-phase agentic system architecture, where protocol documents are first parsed, structured, and embedded into a searchable memory (green), enabling real-time agents (orange) to classify incoming clinical data from the Clinical Trial Management System (CTMS), reason over protocol rules, detect deviations, and escalate issues with human oversight.

Where It Got Complicated

In early tests, the system did what it was built to do. It scanned incoming records, spotted missing data, flagged unexpected medication use, and pointed out deviations that might otherwise have slipped through. On structured examples, it handled the checks with speed and consistency.

But as we moved closer to real trial conditions, the gaps started to show. The agents were trained to recognise rules, but real-world data rarely plays by the book. Information arrived out of order. Visit dates overlapped. Exceptions buried in footnotes became critical. Suddenly, a task that looked simple in isolation became tangled in edge cases.

One of the most frequent problems was handover failure. A deviation might be correctly identified by the first agent, only to be lost or misunderstood by the next. A flagged issue would travel halfway through the chain and then disappear or be misclassified because the follow-up agent missed a piece of context. These were not coding errors. They were coordination breakdowns, small lapses in memory between steps that led to big differences in outcome.

We also found that decisions based on time windows were especially fragile. An agent could recognise that a visit was missing, but not always remember whether the protocol allowed a buffer. That kind of reasoning depended on holding specific details in working memory. Without it, the agents began to misfire, sometimes raising the alarm too early, other times not at all.

None of this was surprising. We had built the system to learn from its own limitations. But seeing those moments play out across agents, in ways that were subtle and sometimes difficult to trace, helped surface the exact places where autonomy met ambiguity and where structure gave way to noise.

A Glimpse Into the Details

One case brought the system’s limits into focus. A monitoring agent flagged a protocol deviation for a missing lab test on Day 14. On the surface, it looked like a valid call. The entry for that day was missing, and the protocol required a test at that visit. The alert was logged, and the case moved on to the next agent in the chain.

But there was a catch.

The protocol did call for a Day 14 lab, but it also allowed a two-day window either side. That detail had been extracted earlier and embedded in the system’s memory. However, at the moment of evaluation, that context was not carried through. The agent saw an empty cell for Day 14 and treated it as a breach. It did not recall that a test on Day 13, which had already been recorded, fulfilled the requirement.

This was not a failure of logic. It was a failure of coordination. The information the agent needed was available, but not in the right place at the right time. The memory had thinned just enough between steps to turn a routine variation into a false positive.

From a human perspective, the decision would have been easy. A reviewer would glance at the timeline, check the visit window, and move on. But for the agent, the absence of a test on the exact date triggered a response. It did not understand flexibility unless that flexibility was made explicit in the prompt it received.

That small oversight rippled through the process. It triggered an unnecessary escalation, pulled attention away from genuine issues, and reminded us that autonomy without memory is not the same as understanding.

How We Measured Success

To understand how well the system was performing, we needed something to compare it against. So we asked clinical reviewers to go through a set of patient records and mark any protocol deviations they spotted. This gave us a reference set, a gold standard, that we could use to test the agents.

We then ran the same data through the system and tracked how often it matched the human reviewers. When the agent flagged something that was also noted by a reviewer, we counted it as a hit. If it missed something important or raised a false alarm, we marked it accordingly. This gave us basic measures like sensitivity and specificity, in plain terms, how good the system was at picking up real issues and how well it avoided false ones.

But we also looked at the process itself. It was not just about whether a single agent made the right call, but whether the information made it through the chain. We tracked handovers between agents, how often a detected issue was correctly passed along, whether follow-up steps were triggered, and whether the right output was produced in the end.

This helped us see where the system worked as intended and where things broke down, even when the core detection was accurate. It was never just a question of getting the right answer. It was also about getting it to the right place.

What We Changed Along the Way

Once we understood where things were going wrong, we made a few targeted changes to steady the system.

First, we introduced structured memory snapshots. These acted like running notes that captured key protocol rules and exceptions at each stage. Rather than expecting every agent to remember what came before, we gave them a shared space to refer back to. This made it easier to hold onto details like visit windows or exemption clauses, even as the task moved between agents.

We also moved beyond rigid prompt templates. Early versions of the system leaned heavily on predefined phrasing, which limited the agents’ flexibility. Over time, we allowed the agents to generate their own sets of questions and reason through the answers independently. This gave them more space to interpret ambiguous situations and respond with a clearer sense of context, rather than relying on tightly scripted instructions. Alongside this, we rewrote prompts to be clearer and more grounded in the original trial language. Ambiguity in wording was often enough to derail performance, so small tweaks, phrasing things the way a study nurse might, made a noticeable difference. We then added stronger handoff signals. These were markers that told the next agent what had just happened, what context was essential, and what action was expected. It was a bit like writing a handover note for a colleague. Without that, agents sometimes acted without full context or missed the point altogether. Finally, we built in simple checks to track what happened after an alert was raised. Did the follow-up agent respond? Was the right report generated? If not, where did the thread break? These checks gave us better visibility into system behaviour and helped us spot patterns that weren’t obvious from the output alone.

None of these changes made the system perfect. But they helped close the loop. Errors became easier to trace. Fixes became faster to test. And confidence grew that when something went wrong, we would know where to look.

What It Taught Us

The system did not live up to the hype, and it was not flawless, but it proved genuinely useful. It spotted patterns early. It highlighted things we might have overlooked. And, just as importantly, it changed how people interacted with the data. Rather than spending hours checking every line, reviewers began focusing on the edge cases and thinking more critically about how to respond. The role shifted from manual detective work to something closer to intelligent triage.

What agentic AI brought to the table was not magic, but structure. It added pace to routine checks, consistency to decisions, and visibility into what had been flagged and why. Every alert came with a traceable rationale, every step with a record. That made it easier to explain what the system had done and why, which in turn made it easier to trust.

At the same time, it reminded us what agents still cannot do. They do not infer the way people do. They do not fill in blanks or read between the lines. But they do follow instructions. They do handle repetition. They do maintain logic across complex checks. And in clinical research, where consistency matters just as much as cleverness, that counts for a lot.

This experience did not make us think agentic systems were ready to run trials alone. But it did show us they could support the process in a way that was measurable, transparent, and worth building on.

What This Taught Us About Evaluation

Working with agentic systems made one thing especially clear. The way most people assess language models does not prepare you for what happens when those models are placed inside a real workflow.

It is easy enough to test for accuracy or coherence in response to a single prompt. But those surface checks do not reflect what it takes to complete a task that unfolds over time. When an agent is making decisions, juggling memory, switching between tools, and coordinating with others, a different kind of evaluation is needed.

We began paying attention to the sorts of things that rarely make it into research papers. Could the agent perform the same task consistently across repeated attempts? Did it remember what had just happened a few steps earlier? When one component passed information to another, did it land correctly? Did the agent use the right tool when the moment called for it, even without being told explicitly?

These were not academic concerns. They were practical indicators of whether the system would hold up under pressure. So we built simple ways to track them.

We looked at how stable the agent remained from one run to the next. We measured how often a person needed to step in. We checked whether the agent could retrieve details it had already encountered. And we monitored how information moved through the system, from one part to another, without being lost or altered along the way.

None of this required complex metrics. But each of these signals told us more about how the system behaved in real use than any benchmark ever did.

4 A Call for Practical Evaluation Standards

If we want reliable ways to judge these systems, we need to start from what happens when they are used in the real world. Much of the current thinking around evaluating agentic AI remains too abstract. It often focuses on what the system is supposed to do in principle, not what it manages to do in practice. But the most useful insights emerge when things fall apart. When an agent loses track of its task, forgets what just happened, or takes an unexpected turn under pressure.

A recent assessment of Sakana.ai’s AI Scientist made this point sharply. The system promised end-to-end research automation, from forming hypotheses to writing up results. It was an ambitious step forward. But when tested, it fell short in important ways. It skimmed literature without depth, misunderstood experimental methods, and stitched together reports that looked complete but were riddled with basic errors. One reviewer said it read like something written in a hurry by a student who had not done the reading. The outcome was not a failure of intent, but a reminder that sophisticated language does not always reflect sound reasoning.

Instead of designing evaluation methods in isolation, we should begin with real scenarios. That means observing where agents stumble, how they recover, and whether they can carry through when steps are long and outcomes matter. It means showing the messy bits, not just polished results. Tools that help us retrace decisions, inspect memory, and understand what went wrong are just as important as the outputs themselves.

Only by starting from lived use with its uncertainty, complexity, and human oversight, can we build evaluation methods that truly reflect what it means for these systems to be useful.

5 Closing Thoughts from the Field

Agentic AI carries genuine promise, but even a single deployment can reveal how much distance there is between ambition and execution. These systems can be impressively capable in some moments and surprisingly brittle in others. And in domains where decisions must be precise and timelines matter, that brittleness is more than an inconvenience; it introduces real risk.

The lessons from our experience were not abstract. They came from watching one system try to handle a demanding, high-context task and seeing where it stumbled. It was not a matter of poor design or unrealistic expectations. The complexity was built in, the kind that only becomes visible once a system moves beyond isolated prompts and into continuous workflows.

That is why evaluation needs to begin with real use. With lived attempts, not controlled tests. With unexpected behaviours, not just benchmark scores. As practitioners, we have a front-row seat to what breaks, what improves with small tweaks, and what truly helps. That view should help shape how the field evolves.

If agentic systems are to mature, the stories of where they struggled and how we adapted cannot sit on the sidelines. They are part of how progress happens. And they may be the clearest indicators of what needs to change next.

- About the authors

- Francis Osei is the Lead Clinical AI Scientist and Researcher at Bayezian Limited, where he designs and builds intelligent systems to support clinical trial automation, regulatory compliance, and the safe, transparent use of AI in healthcare. His work brings together data science, statistical modelling, and real-world clinical insight to help organisations adopt AI they can understand, trust, and act on.

- Copyright and licence

- © 2025 Francis Osei

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) International licence. Thumbnail photo by khunkornStudio on Shutterstock.

- How to cite

- Osei, F. (2025). “Deploying Agentic AI: What Worked, What Broke, and What We Learned”, Real World Data Science, August 12, 20245. URL

::: :::